4 Environmental

The following includes variables that establish the estuarine setting: rainfall, water temperature, and salinity. These variables are driven primarily by climatic patterns and largely influence water quality condition.

4.1 Rainfall

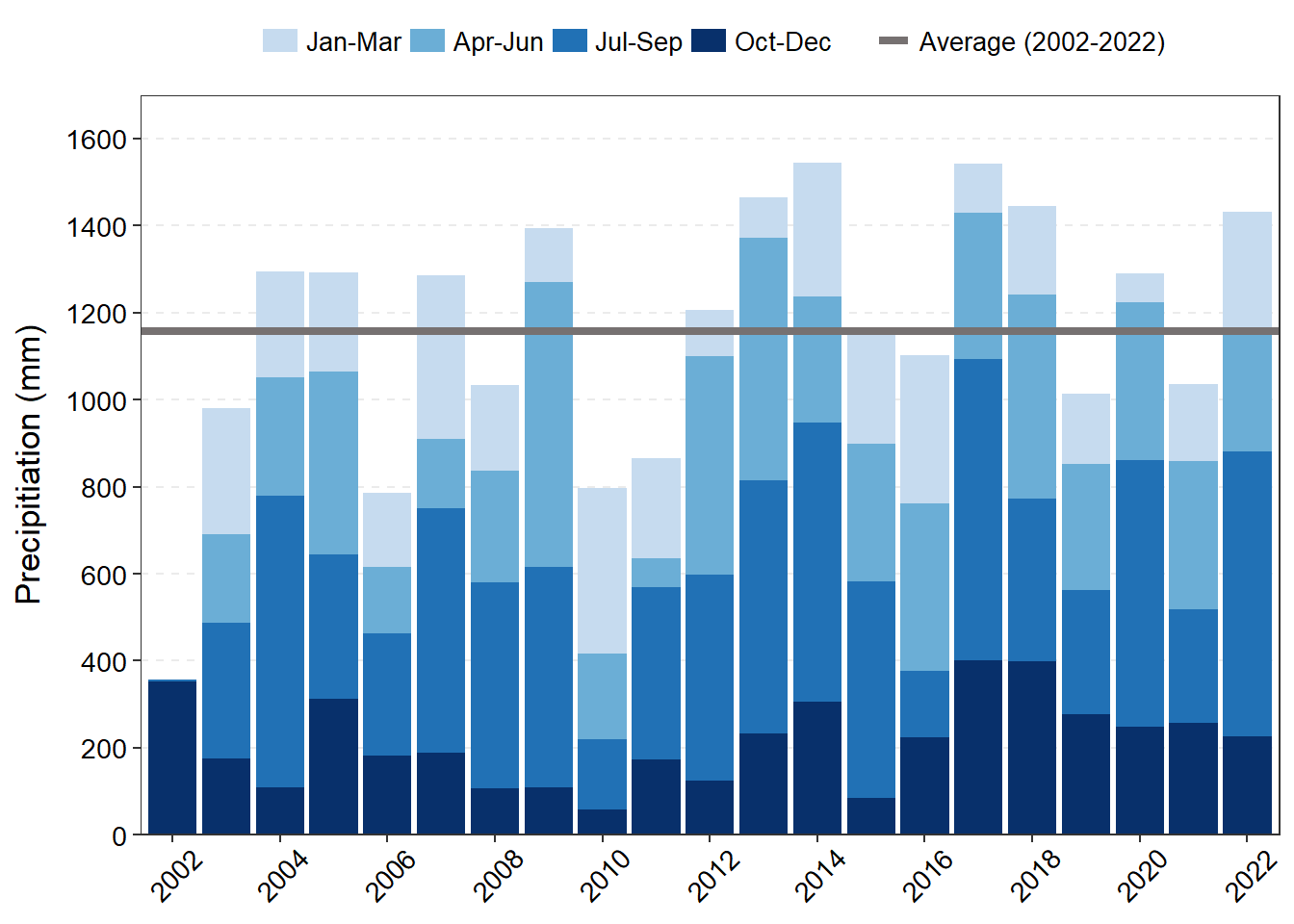

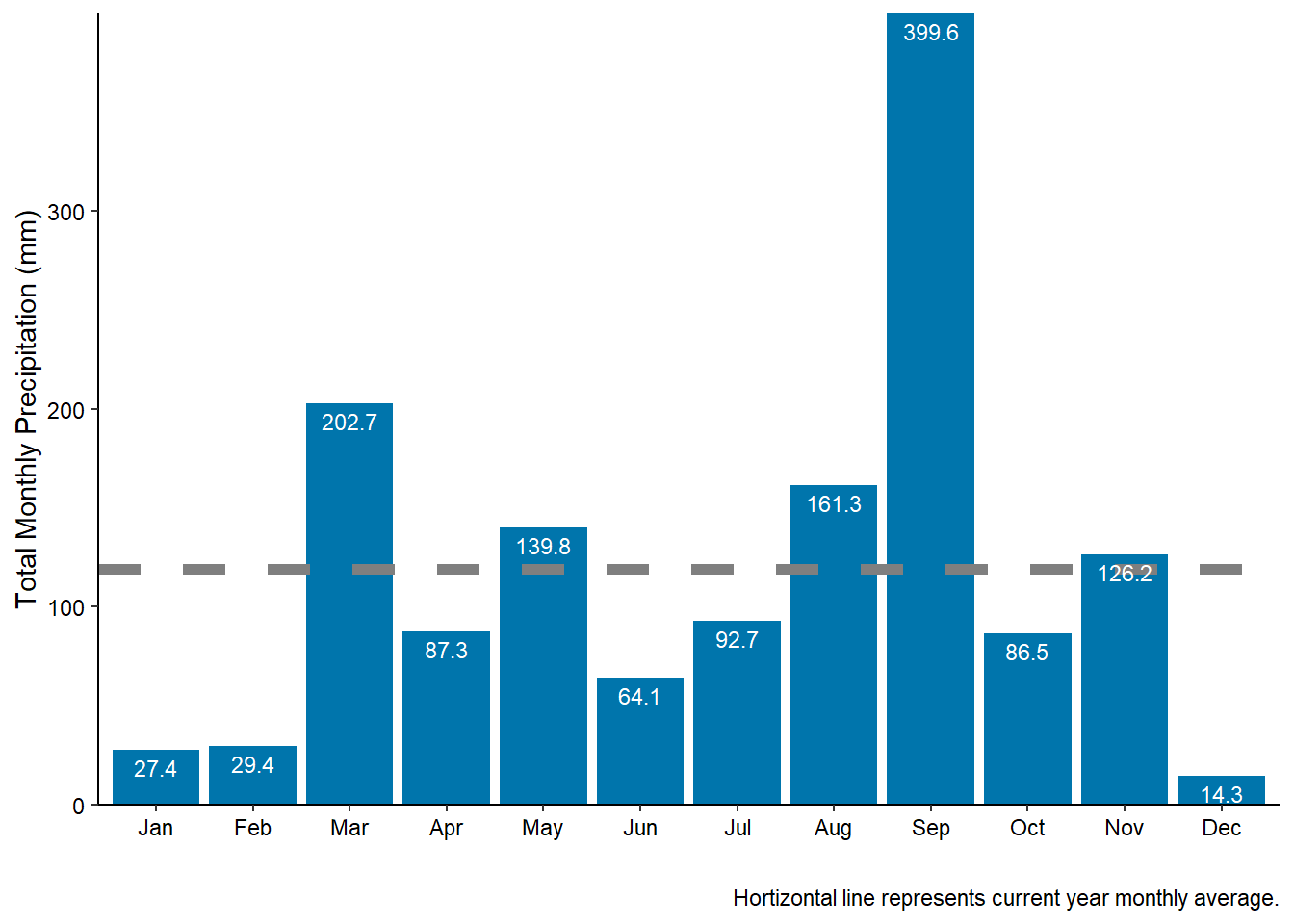

Since the winter “season” in northeast Florida typically spans across years (December of the previous year through February of the following year), quarters are used instead of seasons. In 2022, the GTM Research Reserve weather station recorded much higher rainfall in the first quarter (January-March) than the previous five years (Figure 4.1 (a)). The majority of this rainfall occurred during the month of March with approximately 200 mm (7.87 in) of rain (Figure 4.1 (b)).

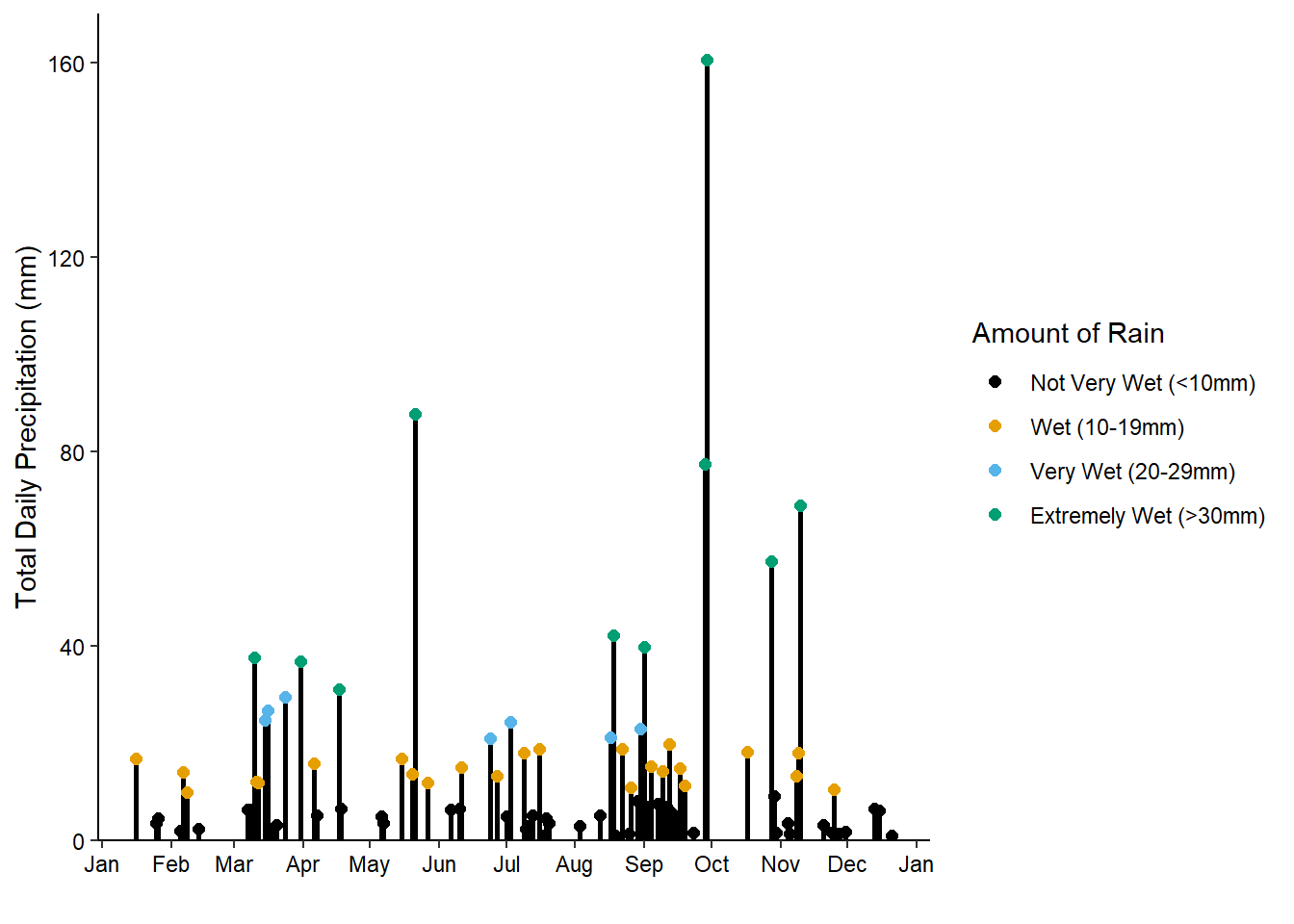

With the exception of a single 24-hr period on May 21, 2022 that resulted in 87.1 mm (3.43 in) of rain, the spring and summer months were rather dry with no “extremely wet” days of rainfall (>30mm) and very few “very wet” days (20-29mm). In fact, mid-July through mid-August saw almost a month with no rainfall (Figure 4.1 (c)). Regular rain resumed in late August into September concluding with extreme precipitation during Hurricane Ian (Chapter 7), which contributed to September having the largest amount of monthly rainfall for the year with 400 mm (15.7 in) of rain.

Even though another tropical cyclone event, Hurricane Nicole (Chapter 8), occurred in November, the fourth quarter rainfall levels were still within similar amounts to the previous few years (Figure 4.1 (a)). The majority of the rainfall in November was associated with Hurricane Nicole and December had the least amount of rain all year, with only 3 days of very little rain (Figure 4.1 (c)).

4.2 Temperature

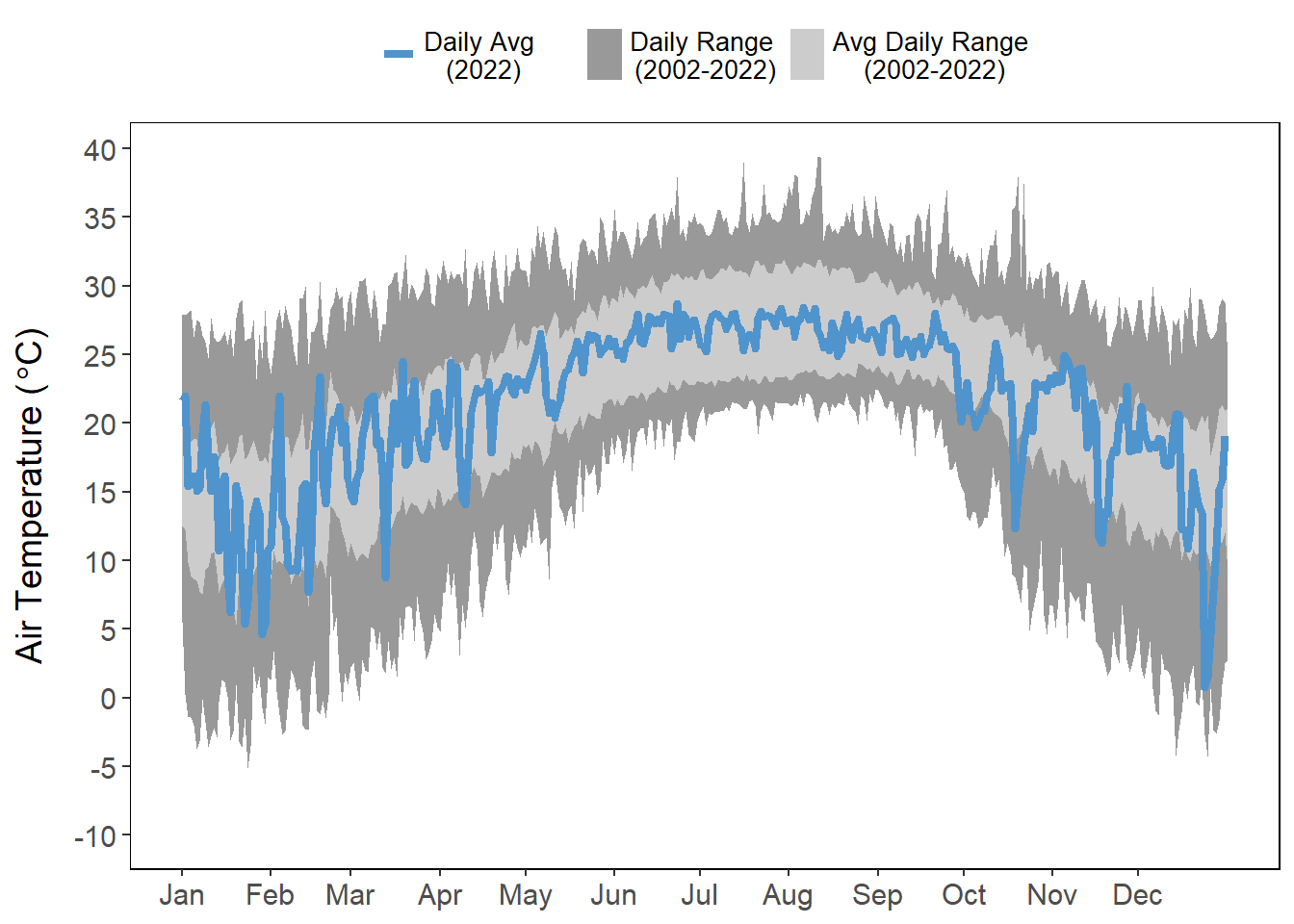

Temperature fluctuations were observed outside of normal ranges several times throughout the year (Figure 4.2 (a)). The most variable ranges occurred in the first quarter of the year with several cold days in January and a very clear drop in temperature with the rainstorms in March 2022. The beginning of January had several hotter than average days. Several distinctive drops in average temperature were observed in the last quarter associated with storm events (Hurricane Ian, Hurricane Nicole, and nor’easters) (Figure 4.2 (a)).

Freezing temperatures are of great interest in northeast Florida because the region is a climatic transition zone experiencing a shift in foundational vegetation species associated with temperature (Zomlefer, Judd, and Giannasi 2006; Williams et al. 2014; Rodriguez, Feller, and Cavanaugh 2016; Cavanaugh et al. 2019). Salt marsh grasses are out-competed by mangrove trees/shrubs in the absence of freezes, which limit mangrove persistence. Mangrove coverage has continued to increase throughout Northeast Florida from an estimated four acres in 1990 to almost 3,000 acres in 2014 (Dix et al. 2021).

Mangroves and salt marsh in wetlands near Washington Oaks Gardens State Park and Matanzas State Forest in St. Augustine, Florida.

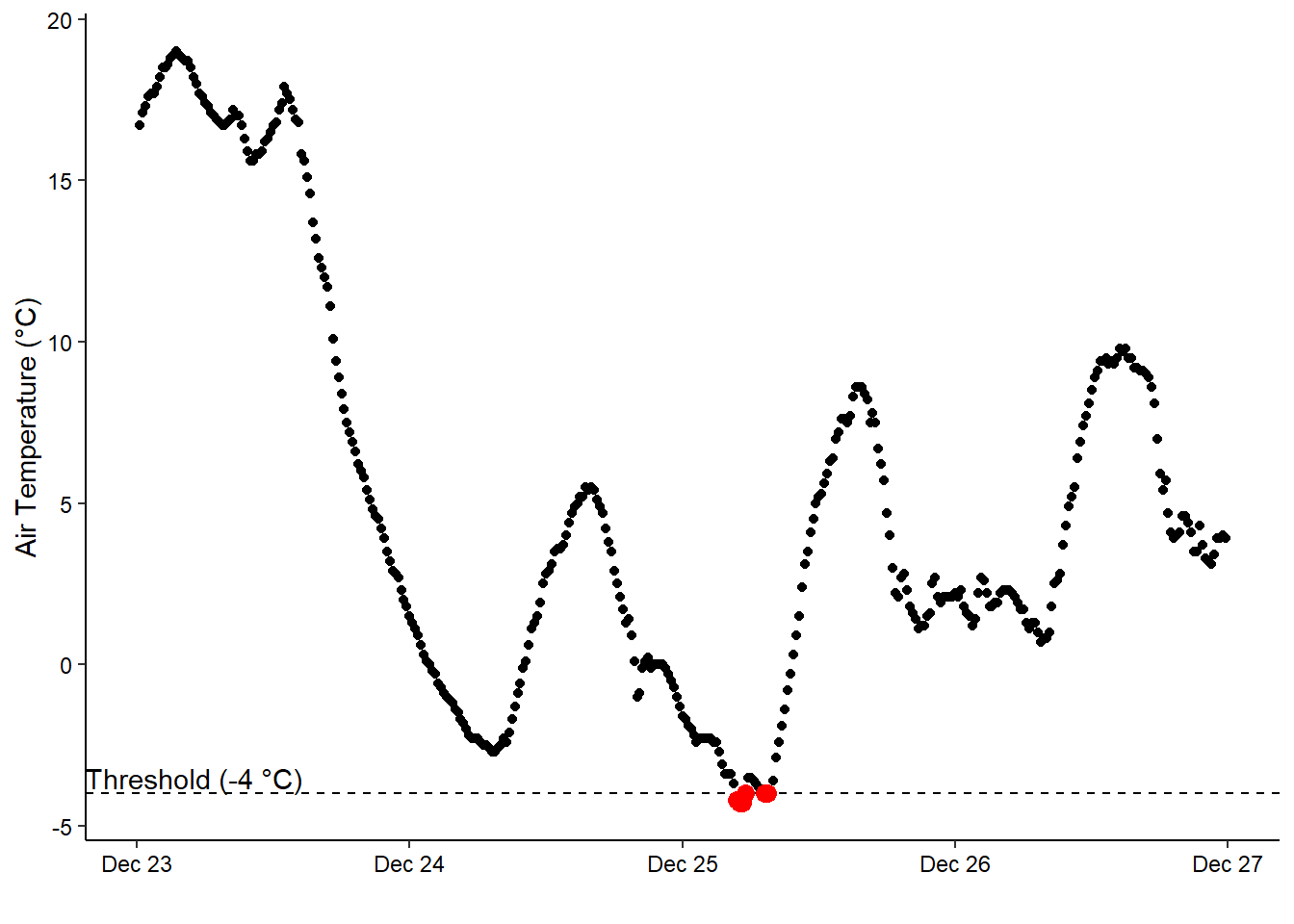

Cavanaugh et al. (2013) observed an ecological threshold of -4 °C, where mangrove cover decreased in years that experienced temperatures below -4 °C. Prior to this year, temperatures at the weather station only fell below -4 °C on two days: January 24, 2003(for 6.5 hours, the longest duration below this threshold) and December 14, 2010. This year, temperatures fell below -4°C early on the morning of December 25th for 3 hours (Figure 4.2 (b)).

Every one of the freeze events (2003, 2010, and this year) occurred in the early morning hours between 4-8 am.

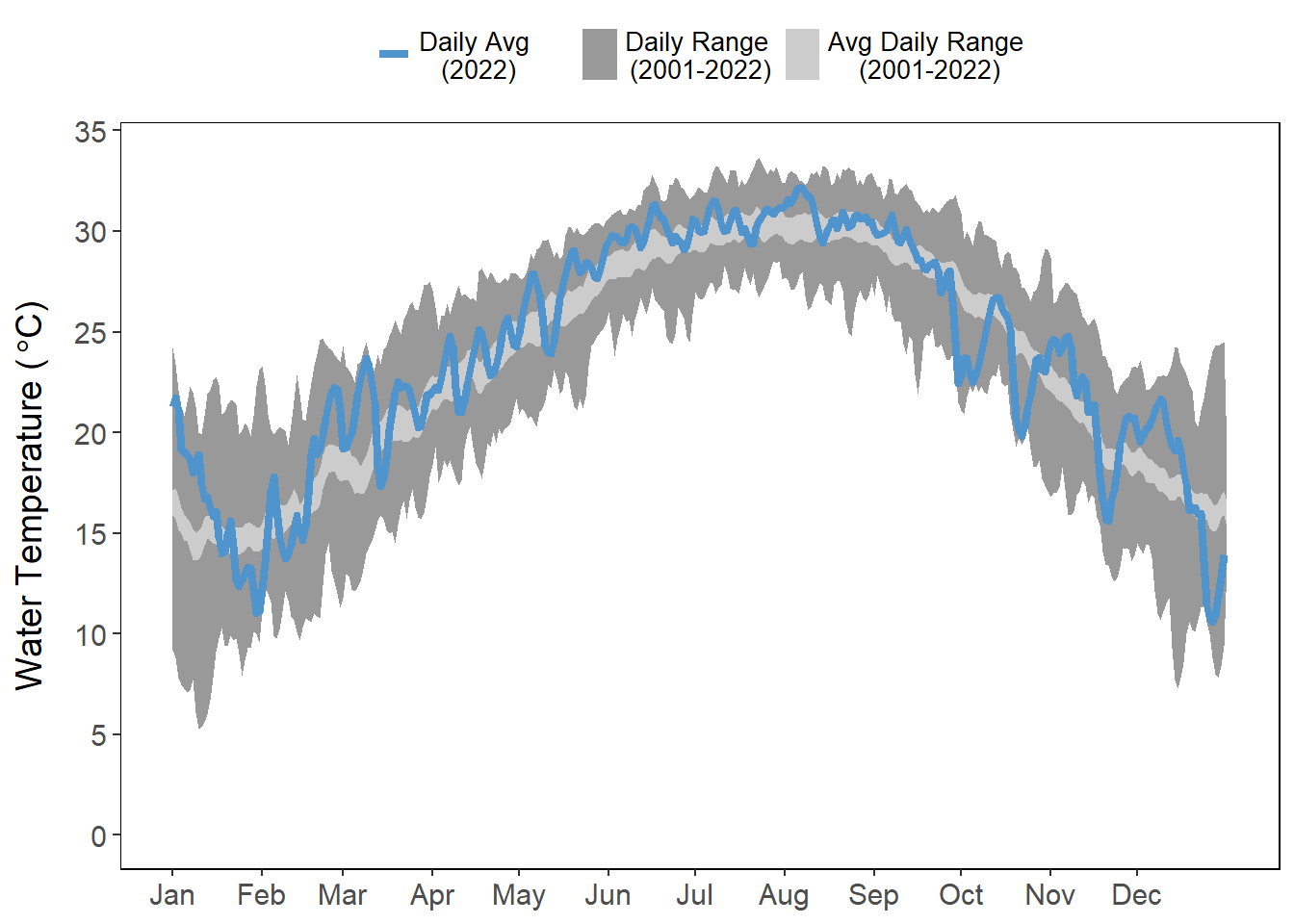

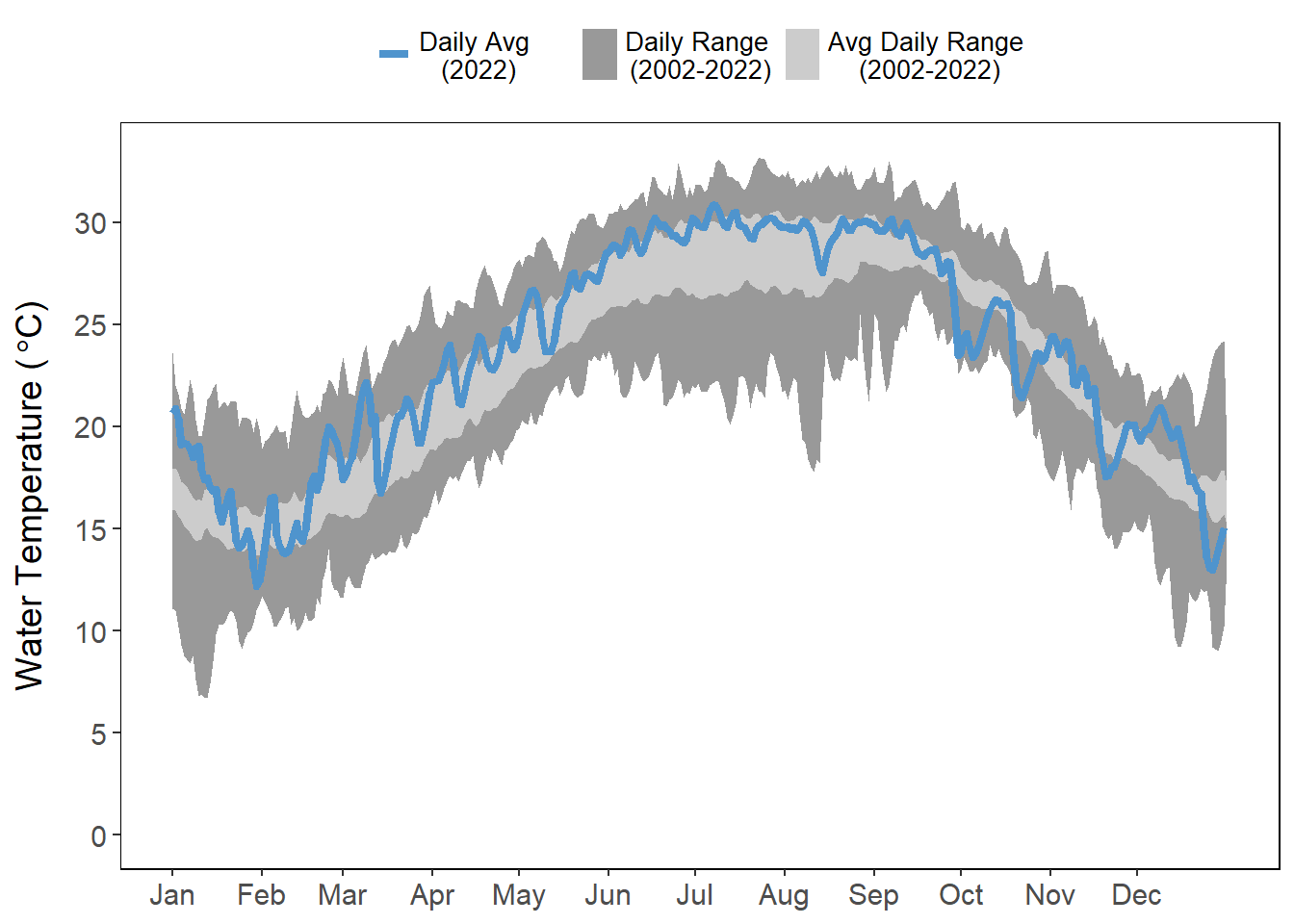

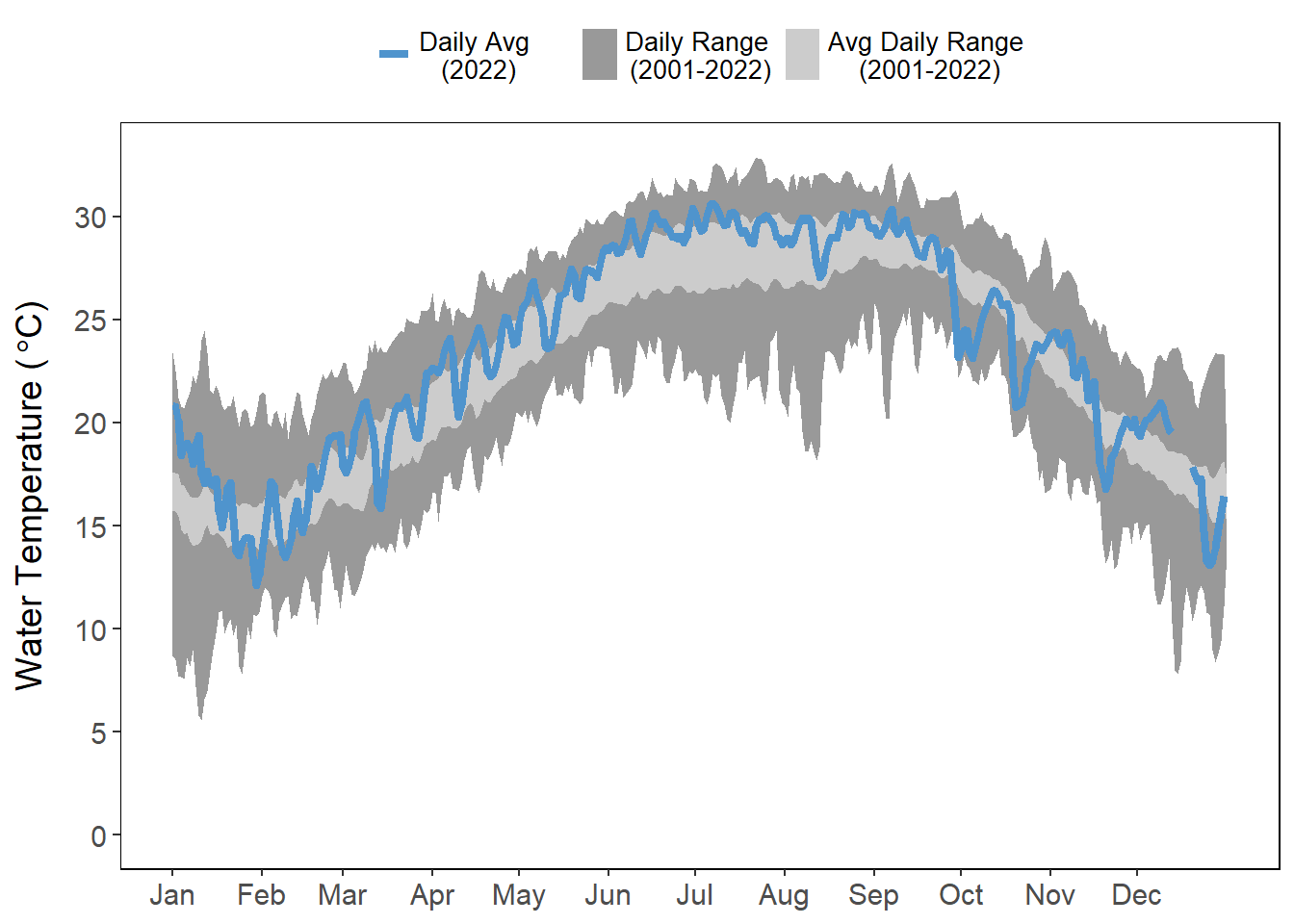

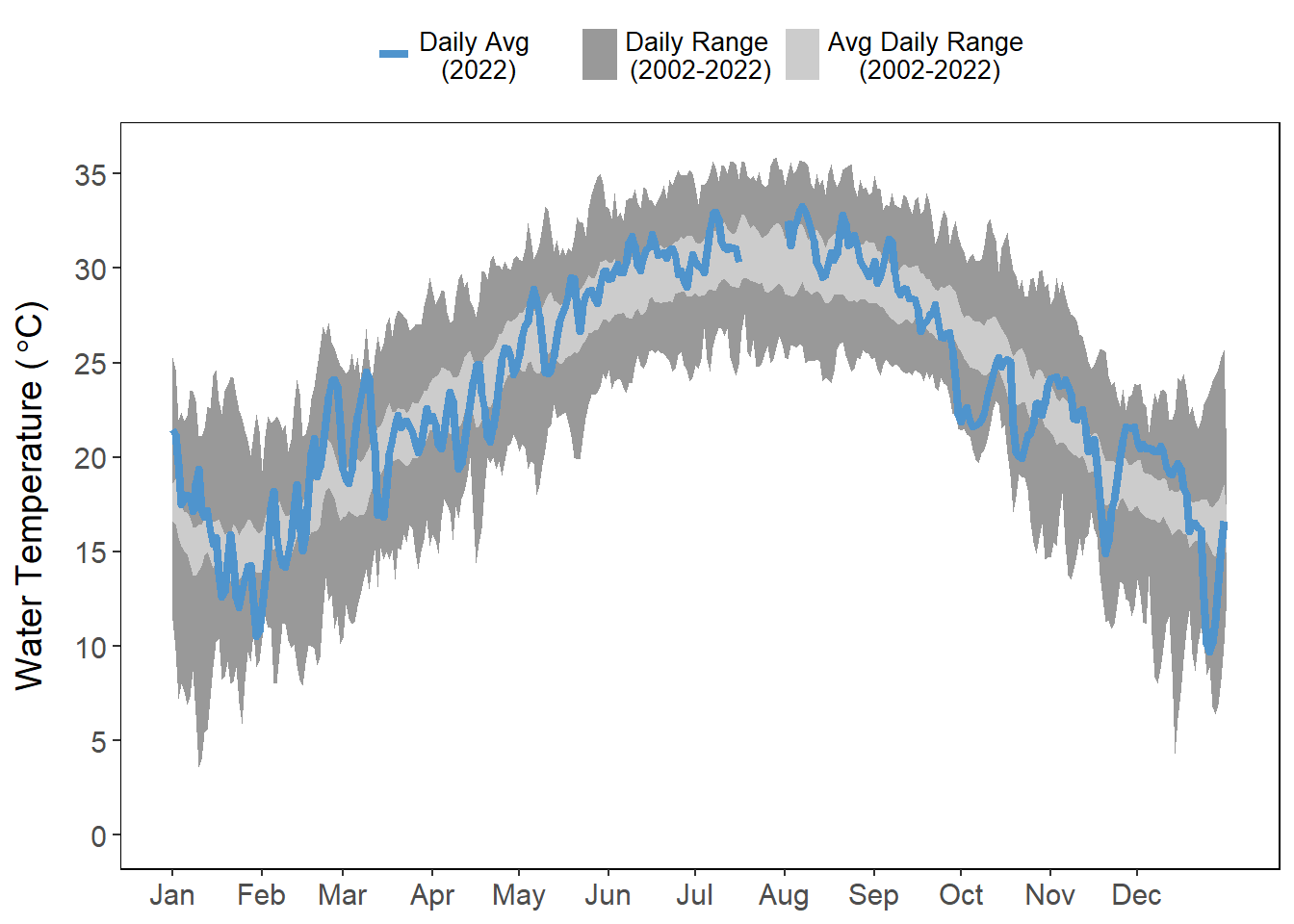

Similar to air temperature, water temperature was also quite variable in the first quarter of the year (January - March) where daily averages were much lower in the end of January. However, water temperatures in March ended up being higher than air temperatures, likely due to the added freshwater from the rains in March (Figure 4.1; Figure 4.3). Water temperatures do not experience the range in values that are observed in the air, although similar observable drops in temperature in the early and late parts of the year were visible (Figure 4.3).

Beginning in the latter part of May through the entire summer, with little to no rain events, waters were much warmer than average, particularly in the shallower sites (Figure 4.3 (a); Figure 4.3 (d)). There was an observable drop in water temperatures at all sites during the time Hurricane Ian struck the Florida peninsula in late September, but temperatures climbed back into their “normal” range after the storm passed at all sites except Pellicer Creek (Figure 4.3), which is a shallow creek and more influenced by upland runoff. At all four stations, there were observable drops in water temperature in October, November, and December (Figure 4.3).

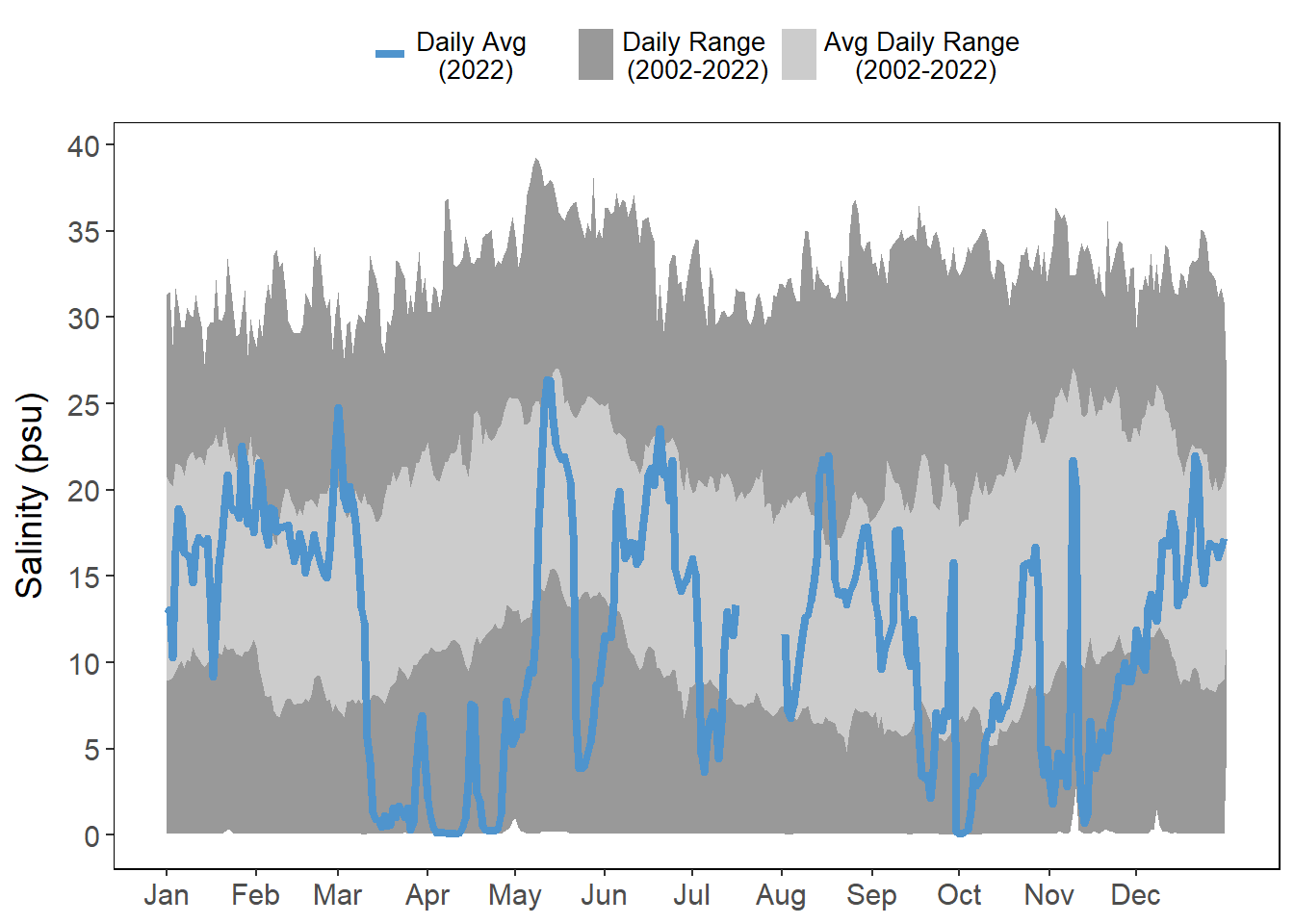

4.3 Salinity

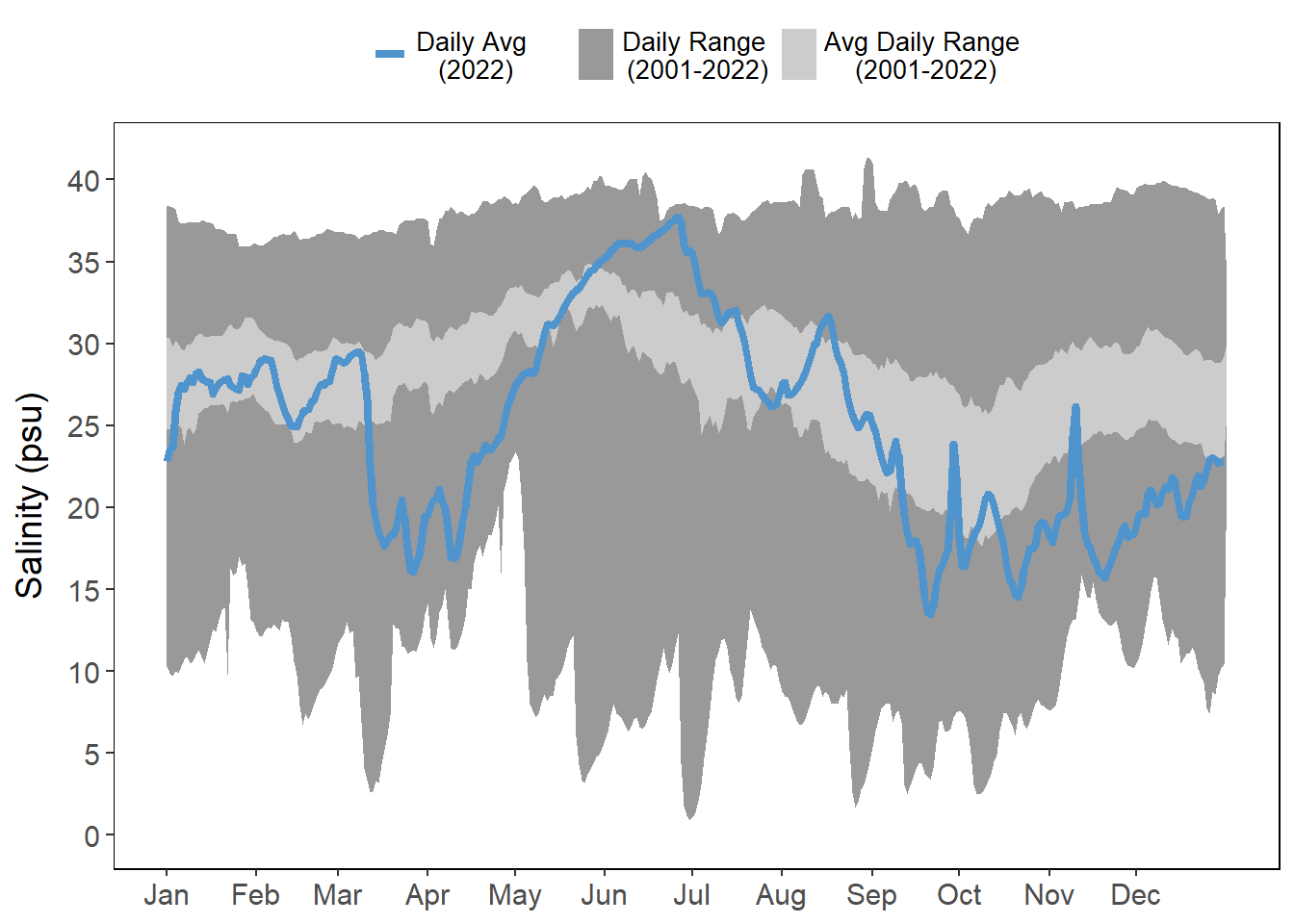

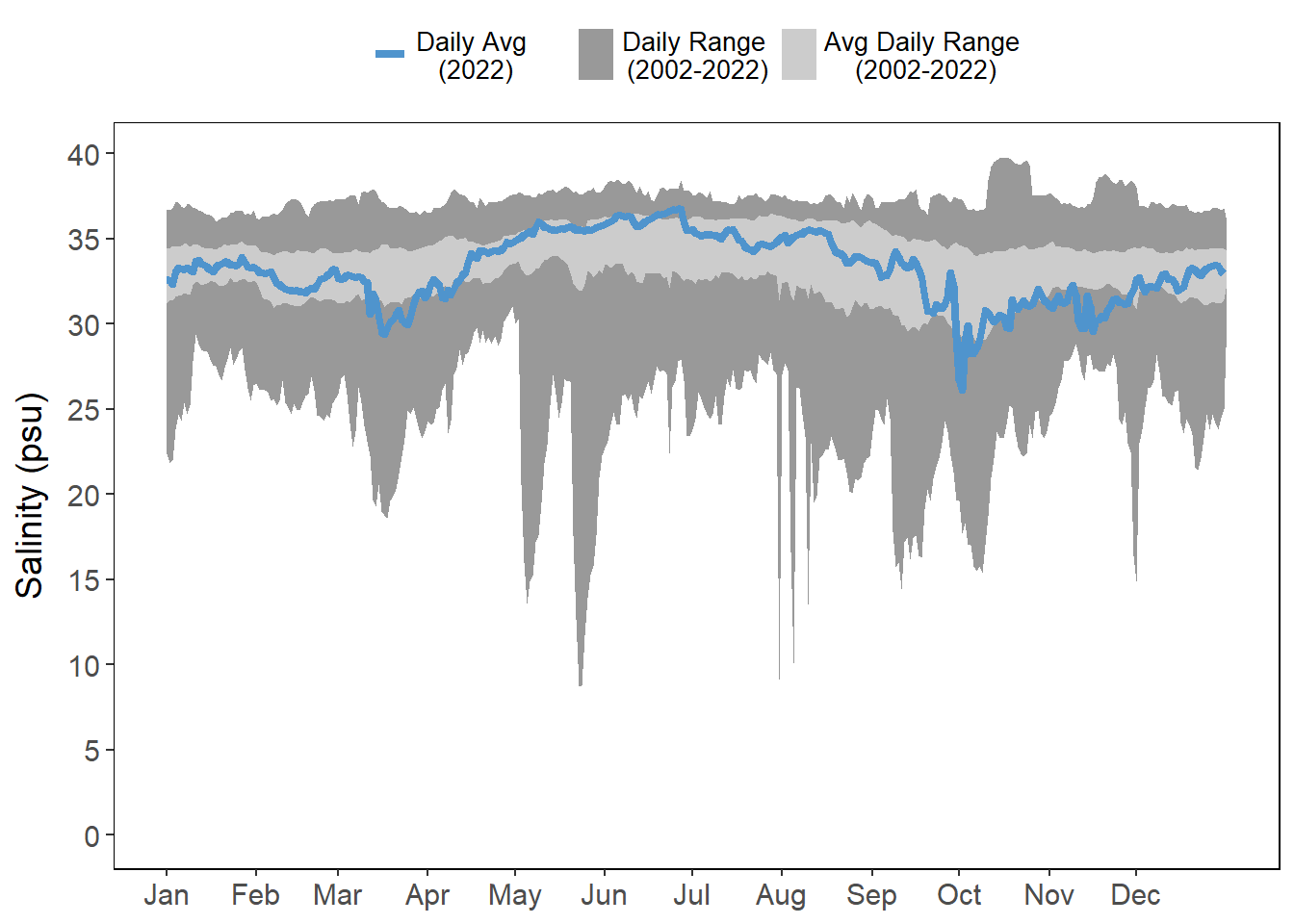

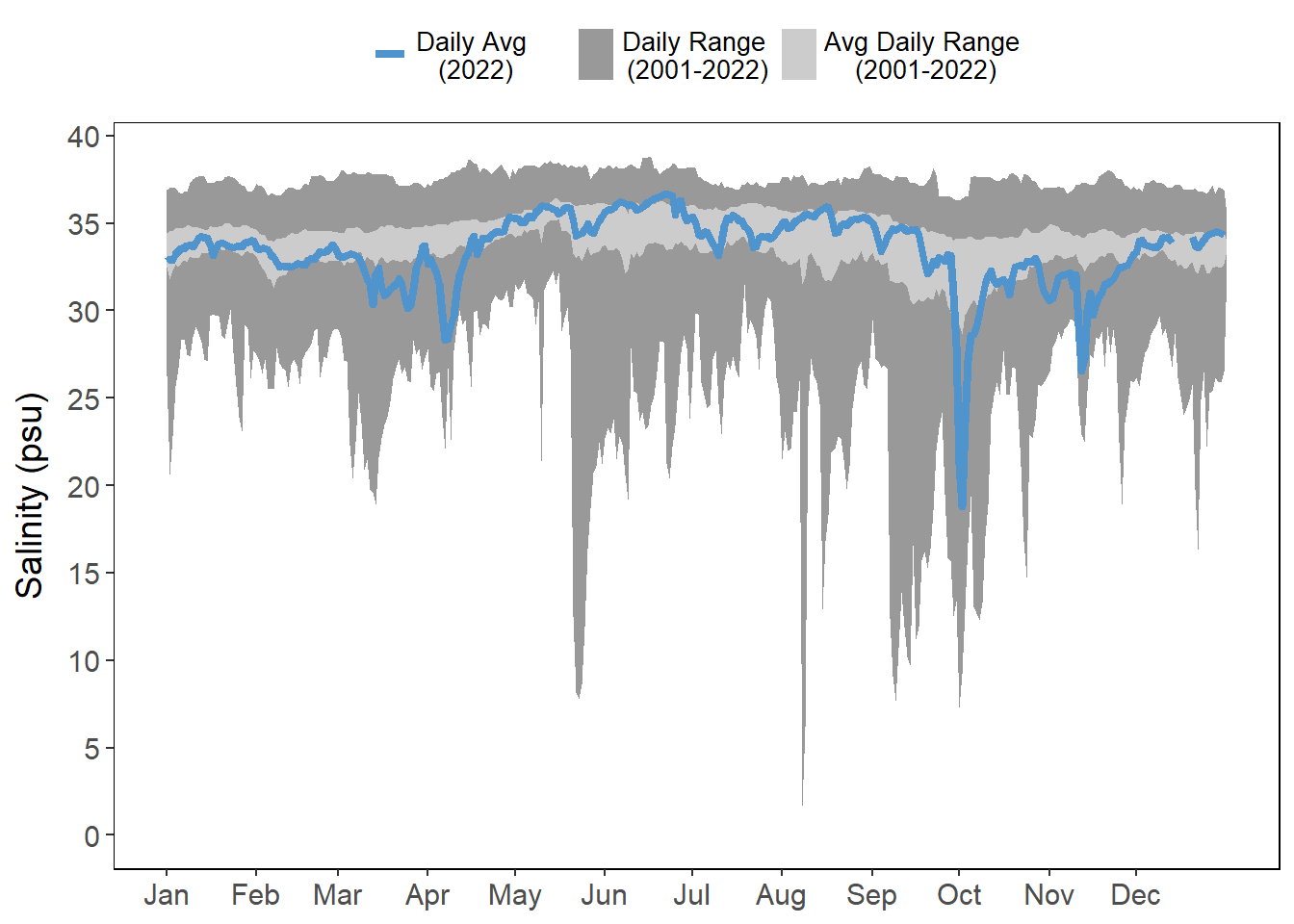

The heavy rainfall in March 2022 and the rainfall associated with Hurricanes Ian and Nicole in late September and November 2022 was evident in the drastic drops in salinity at all stations (Figure 4.4). Due to a lack of rain the late spring/early summer (only 12 days of rain between May 1 and July 1), many of the sites had very high salinities, particularly Pine Island (Figure 4.4 (a)). The rainy periods throughout the year are observable in the salinity data collected in Pellicer Creek with distinct drops in salinity observed during each rain period (March-April, May, early July, late Aug-October)(Figure 4.1 (c); Figure 4.4 (d)).